Actualidad

Advanced Protocols for Accurate Virus Detection in Leafy Greens and Berries

Researchers in Spain develop advanced protocols to detect norovirus and hepatitis A on leafy greens and berries, aiming to minimize false positives and improve global produce safety

Testing for potential virus contamination in produce can be cumbersome because of difficult sampling and concentration processes and chances for false positives.

To that end, Susana Guix, Ph.D., with the University of Barcelona, is leading research to develop more efficient, faster and more accurate human norovirus and hepatitis A virus detection methods for leafy greens and berries. She said:

“It’s very difficult to grow viruses in the laboratory as we do bacteria, so we have to rely on molecular methods to test. If viruses are on produce, they’re usually in very low numbers and at very low concentrations, so we need to have very good extraction procedures."

“Another challenge is if we do get positive (test) results, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there’s a real risk — the virus may be inactivated.”

Guix said the research results are expected to benefit the produce industry by providing a faster method for biological analysis. In addition, the test method should yield a more accurate picture of potential virus risks based on robust data. She said they hope their work also fills critical knowledge gaps about the persistence of infectious viruses on leafy greens and berries during post-harvest storage and during disinfection steps.

Although the work is being conducted in Barcelona, Spain, laboratories, Guix foresees worldwide impacts. Joining her as co-investigator is Gloria Sánchez Moragas, Ph.D., at IATA-CSIC in Valencia, Spain, who brings expertise in developing molecular methods to detect enteric viruses in food and water and monitor inactivation processes. Guix’s lab focuses more on cell culture procedures. Guix said:

“I think the two labs are complementary”.

At times during the research, the two labs ran assays concurrently to provide more robust results.

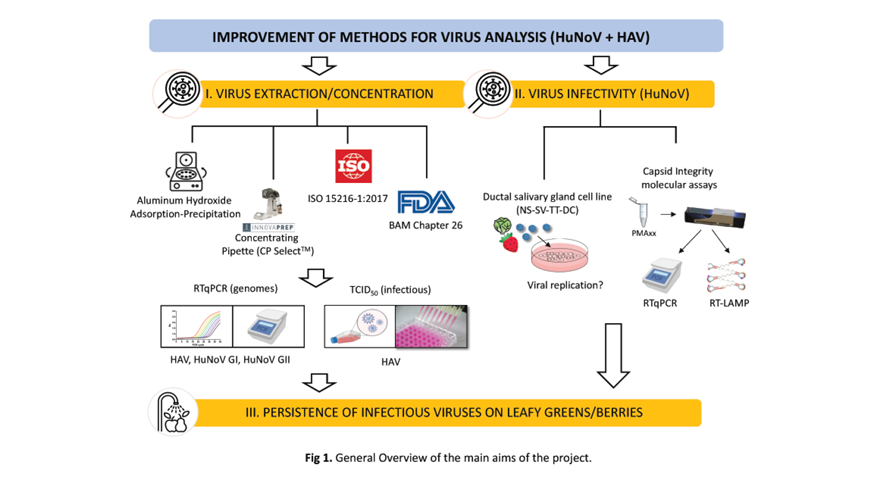

To begin, researchers extracted viruses from the produce surface. If viruses are present, they’re typically in ultra-low numbers so they must be concentrated to prepare for analysis.

As part of the CPS-funded project, they developed two alternative virus extraction/concentration protocols based on one commercially available and one non-commercial method. They tested them against the industry standard Food and Drug Administration and ISO protocols.

The researchers spiked leafy greens and berries with known quantities of human norovirus or hepatitis A virus and then gauged recovery. They found both the FDA and commercial method recovered significantly more of the targeted viruses from leafy greens than the other two methods.

The commercial method also recovered significantly more viruses from raspberries and blueberries than the other three tests. For strawberries, the commercial test performed similarly to the FDA protocol. Guix said of the commercial protocol:

“So far, it’s given us better results for hepatitis A virus and norovirus on six different types of food, and the results are consistent.”

Once virus samples are prepared, testing frequently involves using RTqPCR, a type of molecular assay that looks for specific RNA in a sample as well as quantifies the amount of genetic material. But just because virus RNA is found doesn’t necessarily mean the microorganisms are viable and infectious.

By combining their novel extraction method with modified RTqPCR, the researchers observed a significant reduction in the number of non-viable hepatitis A viruses — or false positives — compared to FDA and ISO protocols.

During the second half of their two-year project, the researchers plan to use their tests to measure die-off of norovirus and hepatitis A virus on berries and leafy greens inoculated with known quantities and incubated under simulated post-harvest conditions.

They also plan to evaluate the virus-reducing efficacy of three commonly used disinfectant washes for leafy greens — chlorine, chlorine dioxide and peracetic acid.

Learn more about this project at the 2025 CPS Research Symposium, taking place in La Jolla, California, on June 17-18.

About CPS

The Center for Produce Safety (CPS) is a 501(c)(3), U.S. tax-exempt, charitable organization focused exclusively on providing the produce industry and government with open access to the actionable information needed to continually enhance the safety of produce.